Iceland: Female Majority in Government

Kristrún Frostadóttir, the new Icelandic Prime Minister leads 7 female and 4 male ministers. She is looking beyond feminism, since Iceland has a long history of female leadership and goes further.

Iceland’s new Prime Minister Kristrún Frostadóttir (36) is currently the world’s youngest head of government, after the election on 30 November 2024. She is a social democrat and leads a coalition government with a total of 7 female ministers and 4 male. Iceland’s current president is also a woman, Halla Tómasdóttir.

Not much news about the women in government in Iceland, though. Iceland elected the first female president in Europe, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, who served as the fourth president of Iceland from 1980 to 1996. She was also the first woman in the world to be democratically elected as president. Having served for 16 years, she is the longest-serving elected female head of state in history.

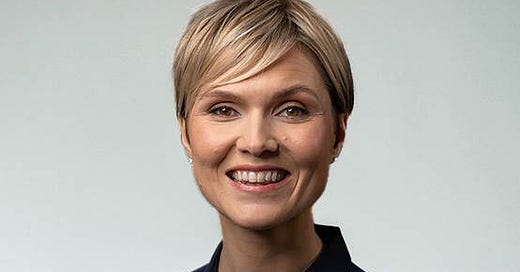

Kristrún Frostadóttir, Prime Minister of Iceland. Photo: Prime Minister's Office

The main themes of the Icelandic general elections were the economy (inflation), housing (prices, high interest rates) and health care. Another big issue was immigration and related asylum seeker issues. Thus, the government of Kristrún has a focus on improving healthcare, reducing housing costs and finding a clear path to a planned referendum on EU membership in 2027.

Iceland has rejected EU membership before. When Sweden and Finland joined in 1995, Iceland was not interested in losing sovereignty and overwhelmingly rejected EU membership. Later, after the so-called Icesave financial scandal in 2008, Iceland applied for and approved for EU membership but gave it up again in 2015.

Similar to Greenland and the Faroe Islands, fisheries weigh in heavily and EU is considered to be very harsh in demanding free access to member states’ fishing grounds. Even if fishing does not really have a dominant position in the UK, it was a big theme in the Brexit debate that Britain claimed back fishing rights. It turned out to be a disaster, among other things because fish for fish and chips come from the North Atlantic, and the local British catches were held up for days in the customs chaos that ensued, blocking the way to the lucrative EU market.

Iceland now has other concerns, such as

Security politics in the new World order, where the North Atlantic is under pressure, especially after Trump’s insistence to have full control of Greenland.

Protection from unplanned surges in migration.

Access to EU stability and development funds.

Having a fair share of attention in the great information wars.

Most of these are better addressed in context of a EU membership, says many politicians and analysts in Iceland. Not all, of course. So a lot of preparation and debate will take place in the next few years, leading to a vote in 2027.

Iceland is a member of NATO, does not have its own military but has a US air base at Keflavik alongside the commercial airport. While having no standing armed forces, Iceland contributes to NATO operations with financial contributions and civilian personnel.

Norse naming convention: Iceland still uses the traditional Norse naming standard without family names, in general. It is Kristrún without Frostadóttir, the latter indicates not the family as such, but says she is the daughter of Frosta. Generally, a person's last name indicates the first name of their father (patronymic) or in some cases mother (matronymic) in the genitive, followed by -son (son) or -dóttir (daughter).

Inclusion as a way of governing, to avoid division, polarization

While Kristrún claims she had no intention of forming a female-dominated government, she has ended up with a coalition run entirely by women. The press, nosy as always, of course nicknamed her government ‘the Valkyries’, her coalition partners are centrist and center-right pro-EU and do not consider themselves activist politicians.

In an interview with the Guardian, the Prime Minister said:

It just so happened that these three parties were run by women. But I do think there is a certain type of dynamic you get when you have three women together. We also have three women who are at a different stage in their lives.

She wants to demonstrate a new way of doing politics. ‘Some of these matters that we’re focusing on have nothing to do with feminism, but it also matters that we can show that you can govern in a different way’ she says. ‘This is a new type of governance – both in terms of political focus, but also in terms of gender.’

Kristrún wants more dialogue with the general public, starting with soliciting suggestions for how to reduce spending and get a balanced budget while preserving a Nordic-style welfare state. Her election was based on a reaction to the preceding government under Bjarni Benediktsson that ended in conflict and split over policy matters, especially the economy.

The new Icelandic government wants to avoid the divisive debate that has led many Western countries into right turns and extremism, as Kristrún sees it. She wants to focus more on listening, rather than becoming judgmental and ‘tell people off’. Politics need to be ‘more humane and less elite’ in order to move away from the extremes in politics.